Watching A Raisin in the Sun and Seeing Red

Modern Drama, 58.4

Abstract

“Watching A Raisin in the Sun and Seeing Red” argues that, while anti-Communism has often been discussed by historiographers of African American theatre, Communism itself and the influence of the Communist Party U.S.A. as a positive force in black theatre history have largely been ignored. As a way of exploring the Communist influence on black theatre, the article describes specific ways in which Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 play is indebted to Communist political critiques. Following the FBI’s own surveillance of the play before it came to Broadway, “Watching A Raisin in the Sun and Seeing Red” also uses the FBI’s own internal memos about the play’s Communist content to reassess the play’s political critique of American individualism, racism, sexism, and capitalism.

The Location’s the Thing: Endstation Theatre and Dramaturgies of Place

Theatre Topics, 25.1 (collaboration with Angela Sweigart-Gallagher)

Opening excerpt

Early in the American classic Walden; or, Life in the Woods, Thoreau writes that “[i]t would be well perhaps if we were to spend more of our days and nights without any obstruction between us and the celestial bodies, if the poet did not speak so much from under a roof, or the saint dwell there so long. Birds,” he says, “do not sing in caves, nor do doves cherish their innocence in dovecots” (345). Thoreau’s words are more than simple musings, of course: the poet issues a direct challenge to his nineteenth-century readers. We might also say that Thoreau’s challenge echoes down the centuries; it resonates in a particularly poignant way in our own technology-savvy, social media–obsessed century. The poet’s words echo, as well, in another American classic: one from the first half of the twentieth century. Emily Webb, after she has painfully revisited her twelfth birthday, asks the stage manager of Our Town if “any human beings ever realize life while they live it.” His answer, after a pause, is: “The saints and poets, maybe—they do some” (Wilder 207). If Wilder proposes that a saint or a poet might truly realize life as he or she lives it, his vision must ideally be located, as Thoreau suggests, under the stars, and as we will suggest, in the hallowed ground of an outdoor performance space chosen, in part, for the way in which the place itself speaks to and through the text: that is, where holiness and poetry are coterminous. This essay is an attempt to answer Thoreau’s challenge and to further echo Wilder; it is a sketch of both sainthood and poetry, and it describes many evenings outdoors under Thoreau and Wilder’s celestial bodies. With a grounded perspective, however, this essay will also aim away from hagiography and toward praxis, in the direction of a practical, even radical dramaturgy of place.

What might we mean by the phrase dramaturgy of place? A definition can become clearer if first we note that by dramaturgy, we mean what Geoff Proehl has called “a play’s poetics or its physics, its nuts and bolts or its flesh and blood.” He further defines the term by referring to “what Mark Lord names when he writes that dramaturgy is the ‘intellectual mise-en-scène, the superstructure or the subconscious (depending on your intellectual heroes) of the idea-world of the theatre event as expressed in its shapes and in its rhythms, and in its affinities with our world’” (27). On the other hand, we intend the word place, following Edward Casey, as more than a descriptor of the general concept of space, but rather as a focused attention to actual location—or as Foucault would have it, emplacement. Casey argues in The Fate of Place that “[t]o be at all—to exist in any way—is to be somewhere, and to be somewhere is to be in some kind of place.” For him, “[p]lace is as requisite as the air we breathe, the ground on which we stand, the bodies we have. We are surrounded by places. We walk over and through them. We live in places, relate to others in them, die in them. Nothing we do is unplaced” (ix). Casey’s work asks us to move away from thinking in terms of the universality of space, instead turning our attention to the specificity that place can offer, to the power and influence of locations themselves.

The Queen’s Cell: ‘Fortune and Men’s Eyes’ and the New Prison Drama

Theatre Survey, 55.2

Opening excerpt

The December 1970 issue of the Canadian newsmagazine Maclean’s features an article by movie critic John Hofsess designed to promote the new film Fortune and Men’s Eyes and to alert readers to that drama’s importance to Canada as a nation. The piece is subtitled “A Report from the Set in a Quebec City Prison” and announces John Herbert’s play Fortune and Men’s Eyes as “the most famous Canadian drama of the last decade—it’s been translated into eight languages and performed in 14 countries.” Hofsess’s first paragraph, however, does not contain Fortune’s list of accolades; instead, the author begins his piece with the following extraordinary narrative:

Two years ago the CBS television program Sixty Minutes reported “a routine incident” in a Philadelphia jail. A white youth, arrested for possession of marijuana and jailed overnight, was gang-raped the next morning by six black convicts in the back of a paddy wagon en route to a courthouse. Police found the boy bleeding and in shock. Such incidents [are] commonly and mistakenly referred to as “the problem of homosexuality in our prisons” [. . .] Yet, statistics indicate that more than 80% of sexual assaults in American prisons are committed by blacks against whites and are motivated by a different lust, a hateful rage that knows no containment.

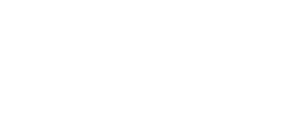

Engaging an Icon: ‘Caroline, or Change’ and the Politics of Representation

Studies in Musical Theatre, 4.2

Opening Section

Tony Kushner and Jeanine Tesori’s 2003 musical Caroline, or Change covers a lot of ground. Kushner, author of the musical’s book and lyrics, creates numerous layers of textual meaning in a musical primarily about motherhood and dealing with loss. Caroline also manages to cover the USAmerican Civil Rights Movement and the assassination of President Kennedy in November 1963, while it turns its main attention to economic structures and poverty in the American South. Though Kushner conceived the show prior to the 2005 Hurricane Katrina disaster, Caroline, or Change is also about the state of Louisiana being under water. Caroline Thibodeaux, the show’s central character, does laundry in a basement in Lake Charles, Louisiana. ‘They ain’t no underground / in Louisiana’, she sings in the opening number; ‘There is only / under water’.

Caroline works as the maid to a middle-class Jewish family in Lake Charles. She cooks and cleans for the Gellmans, and when Noah, the eight-year-old in the house, comes home from school, Caroline watches him. This relationship – of black woman to white child – is central to Caroline, or Change, but it is, further, a relationship integral to the history of the American South. Kushner’s exploration of this connection situates Caroline, or Change as the continuation of a legacy of literature where black women serve as domestic servants and childcare providers for white families. This aspect of the show was almost universally ignored by critics when Caroline, or Change was first staged in 2003. Though Catherine Stevenson has previously discussed this musical as a narrative about mothers and motherhood, I would like to explore the representations of race in Kushner and Tesori’s musical, particularly its portrayal of black women in the South. This essay briefly examines the trope of the mammy in USAmerican literature before turning specifically to Kushner’s treatment of black women in Caroline, or Change. It is my contention that a reading of Caroline, or Change through the historico-cultural lens of the mammy icon further enriches interpretations of the musical at the same time as it repositions the legacy of that icon in our contemporary political moment. I argue that Kushner and Tesori’s musical, through a critical engagement with the mammy trope, creates a rich and dynamic portrait of a black woman that reclaims and revitalizes the mammy as a unique USAmerican cultural icon and a powerful force for political change.