“A Gender of One; a Sexuality of Many: Hedwig and the Practice of Identity”

Opening Section

In hindsight it is not at all coincidental that the journal TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly announced its first issue in July 2012 at the same time as negotiations were underway to mount a Broadway revival of the musical Hedwig and the Angry Inch and just eleven months before Neil Patrick Harris was finally announced as the show’s star in June 2013. In their introduction to the first volume of the journal Paisley Currah and Susan Stryker describe (in quotation marks) the “‘transgender turn’ in recent affairs” and articulate their hopes that the journal will be able to analyze that turn in depth in its future volumes.[1]

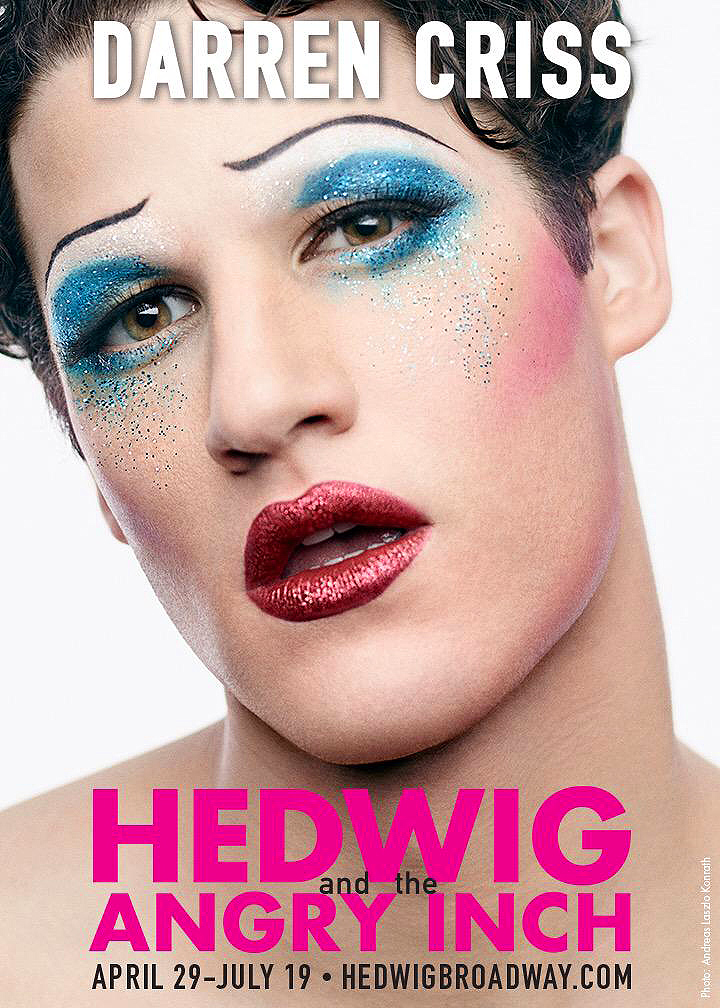

Hedwig and the Angry Inch began previews on Broadway on March 29, 2014 and ran until September 13, 2015 after more than 500 performances. Hedwig then went on a national tour.[2] This period of time between June 2013 and September 2015 was a watershed moment for trans* issues in the United States: Chelsea Manning came out as transgender in August 2013; U.S. Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter made a statement in February 2015 that led to the Obama administration’s inclusion of trans people in the military; and Caitlyn Jenner’s Vanity Fair cover story “Call Me Caitlyn” appeared in the magazine in June 2015.

At the same time, the apparently vexed question of transgender bathroom use rocked the nation, as Arizona, Kentucky, Florida, and Maryland debated so-called “bathroom bills” during the election cycle in 2015.[3] 2015 was also the most fatal year on record for trans people in the U.S. According to a Human Rights Campaign report released in November, “more transgender people were killed in the first six months of this year than in all of 2014.”[4] Since 2015, fatal violence affecting trans people of color, primarily black trans women, has remained at extremely alarming rates.[5] Meanwhile, actress Laverne Cox became the first trans person to appear on the cover of Time magazine in June 2014 and in July became the first transgender actor to be nominated for an Emmy award.[6] The comedy Transparent also debuted on Amazon in 2014, and many commentators saw this as television’s “trans tipping point.”[7]

I map the details of this “transgender turn” because if Hedwig’s first appearance at the Jane Street Theatre in 1998 was shocking, punk, and “unapologetically genderqueer,” Hedwig’s appearance at the Belasco Theatre coincided with an astounding rise in trans visibility – for some trans people – as well as with the apparent ubiquity of trans* issues in LGBT media and other media aimed at queer consumers.[8] This ostensible coincidence is, of course, no coincidence at all, and this essay argues that theatre history, via Hedwig, is an excellent window into trans* issues and LGBT politics in the years 2013-2016. In 2014 Hedwig and the Angry Inch went mainstream, and that popularity is an intriguing marker not of how far we’ve come along the path of progressive politics, but of which path those politics have taken.

My interest today is in the question of casting, where I’d like to look, especially, at the way the actors who played Hedwig understood themselves in relationship to her. This essay begins with the assumption that Hedwig fails as good transsexual representation – as Jordy Tackitt-Jones has convincingly argued in “Hedwig’s Six Inches” – and I wish neither to argue with his conclusions nor to dwell on them for too long. But if, as Tackitt-Jones argues, Hedwig is not a transsexual woman – and this makes sense; she never claims that identity – her performance and the stories she tells allow for possible points of identification for a multitude of people with differing gender identities. What Hedwig perhaps offers us (from her unique position – a gender of one) is the possibility of inclusion without identity or of a more capacious identity defined only by gender difference or gender diversity. I will conclude today by developing an argument about how Hedwig’s moment on Broadway charts a larger shift in LGBT politics in the U.S.

[1] Paisley Currah and Susan Stryker, “Introduction,” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 1.1-2 (2014): 1-18, at 3. Hedwig also appears in Stryker and Stephen Whittle’s introduction to The Transgender Studies Reader, (London: Routledge, 2006), 1-17, at 8.

[2] The National Tour lasted from October 2016 through July 2017.

[3] Katy Steinmetz, “Everything You Need to Know about the Debate over Transgender People and Bathrooms,” Time, 28 July 2015, time.com/3974186/transgender-bathroom-debate/

[4] Human Rights Campaign, Addressing Anti-transgender Violence: Exploring Realities, Challenges and Solutions for Policymakers and Community Advocates, 2019, assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/HRC-AntiTransgenderViolence-0519.pdf

[5] Gina Martinez and Tara Law, “Two Recent Murders of Black Trans Women in Texas Reveal a Nationwide Crisis, Advocates Say,” Time, 12 June 2019, time.com/5601227/two-black-trans-women-murders-in-dallas-anti-trans-violence/

[6] Aleksandra Gjorgievska and Lily Rothman, “Laverne Cox Is the First Transgender Person Nominated for an Emmy – She Explains Why That Matters,” Time, 10 July 2014, time.com/2973497/laverne-cox-emmy/

[7] Joy Press, “Pose’s Rise, Transparent’s Bittersweet Finale, and the State of Transgender Representation on TV,” Vanity Fair, 13 August 2019, www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2019/08/the-state-of-transgender-representation-on-tv

[8] Caridad Svich, Mitchell and Trask’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch, (London: Routledge, 2019), 22.